California

Department of Forestry and Fire Protection

Review Report of Serious CDF Injuries, Illnesses, Accidents

and Near-Miss Incidents

Engine Crew Entrapment, Fatality, and Burn Injuries

October 29, 2003

Cedar Fire

CACNF-003056

CACSR-000132

Southern Region

GREEN SHEET

(72-hour report)

A Board of Review

has not approved this Summary Report. It is intended as a safety and

training tool, an aid to preventing future occurrences, and to inform

interested parties. Because it is published on a short time frame, the

information contained herein is subject to revision as further investigation

is conducted and additional information is developed.

The CDF Green Sheet

on the Cedar Fire was published without comments from Novato Fire District

Captain Doug McDonald.

SUMMARY

The Cedar Fire was reported on Saturday, October 25, 2003, at approximately

5:37 P.M. The fire, burning under a Santa Ana wind condition eventually

consumed 280,278 acres and destroyed 2,232 structures, 22 commercial buildings,

and 566 outbuildings, damaging another 53 structures and 10 outbuildings.

There was 1 fire fighter fatality, 13 civilian fatalities and 107 injuries.

The fire was under Unified Command with the United States Forest Service,

the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, and local government.

On October 29, 2003 four personnel from Engine Company 6162 (E6162) of

the Novato Fire Protection District, as part of Strike Team XAL2005A,

were overrun by fire while defending a residential structure located on

Orchard Lane in the community of Wynola, in rural San Diego County.

The fire made a wind-driven run through heavy brush directly toward their

position, covering a distance of approximately one-half mile in just less

than two minutes. One crewmember died at the scene and the three others

were provided treatment and then airlifted to the University of San Diego

Burn Center.

CONDITIONS

The accident site was located on a ridge near the origin of the San

Diego River drainage. Slopes at the accident site range between 12-20%.

The elevation at the accident site is approximately 3800 feet, 400 feet

above the bottom of the drainage.

The Palmer Drought Index shows a preliminary reading of -2.88. The fuel

models in the immediately area of the accident site were Fuel Model 4-brush

(with at least 90% crown closure) and Fuel Model 1-grass. Live fuel moisture

values were below critical levels.

At the time of the accident a strong onshore pressure gradient had developed

with sustained winds of 17 mph and a gust of 31 mph out of the west. At

2:30 P.M. at the accident site the temperature was 70 degrees and the

relative humidity was 30%.

As all the fire environment factors of fuel, wind and topography came

into alignment there was a sustained run from the southwest directly to

the accident site as a running crown fire. Flame lengths were calculated

to be in excess of 78 feet, fire line intensities in excess of 73,989

BTU/ft/sec, and rates of spread in excess of 16 miles per hour (for the

maximum wind speed recorded at 31 mph). It took the fire a little under

2 minutes to go from the bottom of the slope to the top, a distance of

.46 miles. All fuels, both dead and live were totally consumed below the

accident site.

Road Conditions: The access to the accident site is a curving ten-foot

wide, 490-foot long cement driveway proceeding uphill to the residence.

The driveway is overgrown with brush and requires trimming to allow ingress.

At the ridge top, the driveway makes a sharp 90 degree curve to the south

that finally orients in line with the ridge along the west side of the

house.

Make/Model of Equipment: E6162 is a series 2000 International similar

to a CDF Model 14. It is outfitted with a 4-person cab; 500-gallon tank

and a 500 gallon-per-minute (GPM) pump. The engine is 8 feet 8 inches

wide, 24 feet long, and 9 feet 4 inches tall.

SEQUENCE OF EVENTS

By 11:00 A.M. on October 29, 2003, the Cedar Fire had crossed Highway

78 spreading along the ridge on the west side of the San Diego River drainage.

The fire was making short runs (averaging less than 100 yards) in the

grass, brush and oak trees. Helicopters were making bucket drops in an

effort to keep the fire on the west side of the San Diego River drainage.

The fire on the west side of the drainage moved up canyon and gained

elevation. Under the influence of a west wind, higher up in the drainage,

the spread to the northeast, burning the property at 902 Orchard Lane.

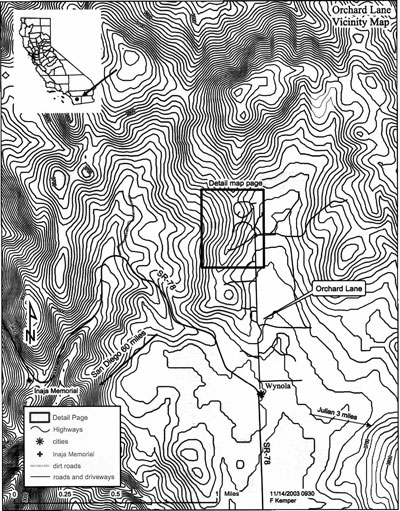

(See Fire Spread Map) Spot fires are observed in the area and both helicopters

and ground resources are moved to the area of Orchard Lane. This includes

ST2005A, with E6162, which has a four-person crew including a Captain,

two Engineers (who will be referred to as Engineer #1 and Engineer #2)

and a Fire Fighter.

At about 12:15 P.M., the Strike Team Leader for 2005A, after reviewing

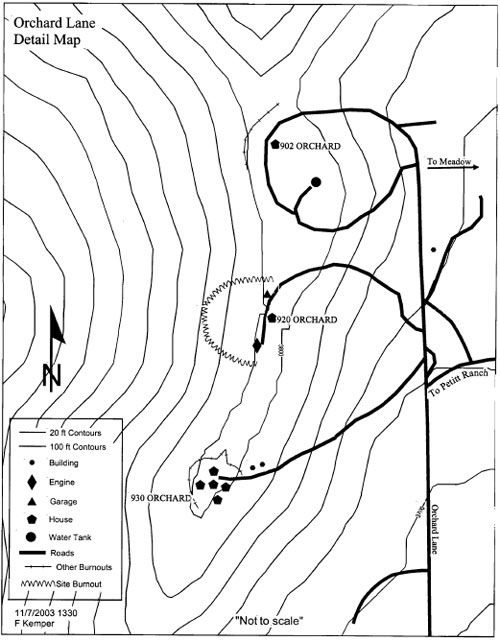

conditions, assigns E6162 to the residence at 920 Orchard Lane (the site

of the accident). No engines are assigned to 902 or 930 Orchard Lane.

(See Orchard Lane Detail Map) A Captain and an Engineer, in a utility

vehicle, arrive at 902 Orchard Lane and begin to fire out around the residence.

While the Captain from E6162 walks ahead to evaluate, E6162 backs up

the driveway as overhanging brush is cleared by the crew of E6162. (See

Accident Site Sketch) The Captain returns to the engine and expresses

some concern about the conditions. The Captain and Fire Fighter return

to the residence and determine, based on a large cleared area to the southwest

side of the property, that the location is defendable.

The cleared area provides for a view to the west and northwest, tall

brush and drifting smoke restricts the view to the southwest and no fire

activity is visible. They observe smoke from the fire to the north, near

902 Orchard Lane, which is flanking towards them, and determine it to

be the greatest threat. Small runs of fire are taking place across the

canyon on the west side of the drainage.

The crew observes an up-canyon and up-slope wind, at about 7-10 mph,

on a line from where Highway 78 crosses the San Diego River towards the

location of 902 Orchard Lane, a natural saddle. The crew develops and

implements a plan that includes: brushing and firing below the house;

identifying the house and/or engine as a refuge and placing an axe at

the back door; using a residential ladder on the house; laying out 11/2"

hose lines for engine protection all in an attempt to defend the structure.

The Captain advises the crew of a fire fighter firing out in the area

north of the garage. Engineer #1 observes fire on the ground near the

garage, and begins strip firing from that location. The Captain throws

fusees down the slope into the heavy brush below the area strip burned.

This results in a partial burn.

At about 12:25 P.M. the Captain and Engineer, in the utility vehicle,

arrive at 930 Orchard Lane. They begin firing around the structures from

south to north along the west side of the structures. The Captain instructs

the Engineer to take the line of fire to the next house to the north,

which is 920 Orchard Lane. The Engineer begins to lay fire towards the

north in 15-foot brush with dry grass underneath. Active burning conditions

result from this firing and the Engineer does not continue north. Fire

from the firing operation makes a run east towards the driveway, where

a helicopter bucket drop slows it down.

At about 12: 35 P.M. the Strike Team Leader for 2005A arrives at the

location of E6162 and reviews their progress and plans. The sky is clear

overhead and the winds are moderate. About five minutes after the Strike

Team Leader leaves the scene, the crew of E6162 observes an increase in

the fire activity below them.

Near where Highway 78 crosses the San Diego River, the fire begins an

up-canyon, up-slope run in heavy brush and oak fuels. Wind driven, the

fire makes a continuous run directly at 920 Orchard Lane, covering a distance

of about one-half mile in les than two minutes. (See Fire Spread Map)

As the fire intensity below them increases the crew retreats to the passenger

side of the engine. The Fire Fighter staffs a 11/2" hose line at

the front bumper, while Engineer #2 staffs a similar hose line near the

rear bumper. Engineer #1 is standing at the rear duals. The Captain is

believed to be towards the rear of the engine with the only portable radio.

Members of the crew notice a significant wind increase at this time.

A flaming front is observed blowing across the driveway in the direction

of the garage. Very active fire is observed below them with flame lengths

of 40'-50'. Due to intense heat, the Captain orders the crew to move to

the shelter of the residence. (See Accident Site Detail Map)

Bushes along the patio behind the crew are burning. The Fire Fighter

drops his line and runs in the direction of the raised patio. Upon leaving

the protection of the engine he experiences severe thermal conditions.

The Fire Fighter leaps past the burning bushes and onto the patio, followed

by Engineer #1 who runs to the steps, stumbles and falls to his knees

at the top of the steps, recovers, and continues to retreat behind the

rear of the house, following the Fire Fighter. Engineer #2 puts on a hose

pack stored in the rear compartment of the engine.

Arriving at the rear door, (approximately 170' from the engine) the Fire

Fighter and Engineer #1 use the axe to force entry into the residence.

Realizing that no one else is following them, they decide to return and

look for the Captain and Engineer #2. At about this time, a radio call

is heard indicating a fire fighter is down. Fire burns the charged hose

lines (at the rear of the engine) causing the tank to be pumped dry.

The Fire Fighter and Engineer #1 return to the south end of the house.

As they near the southeast corner they observe solid flame blowing sideways

across the patio. They then see the Captain stagger around the corner

out of the flames. He appears to be dazed.

The Captain tells them that Engineer #2 has fallen and states they need

to go back for him, the Captain then turns to go back after the fallen

engineer. Engineer #1 and the Fire Fighter determine the patio area is

untenable. The three retreat back into the residence. Inside they discuss

a plan to search for Engineer #2.

After a moment, they open the front door to check the front of the house.

Intense heat surges in and the door is closed. After a few minutes, a

second attempt is made to try the front door. Engineer #1 exits to search

for the missing Engineer followed by the Fire Fighter who turns back when

he is hit by a burst of heat.

Engineer #1 moves towards the front bumper line taking small shallow

breaths. Engineer #1 observes the body of Engineer #2 on the patio and

continues to the bumper line, advancing it towards the body of the down

Engineer. Engineer #1 gets a 10-15 second burst of water before the tank

is dry.

An increase in heat forces Engineer #1 to take shelter inside the engine.

Engineer #1 considers deploying the extra fire shelters stored in the

cab. Concerned that the Fire Fighter and Captain may come searching for

him, Engineer #1, taking a single breath runs to the front door and rejoins

the other two.

The burning structure forces the three to make their way to the engine.

The Fire Fighter disconnects the two protection lines. Engineer #1 drives

the engine down the driveway to the east. Heavy dark smoke obscures the

view and Engineer #1 feels his way, using the feel of the tires dropping

off the edge of the pavement to make corrections. At one location the

engine is stopped to avoid running off the driveway. Concern about being

overrun again convinces them of the need to continue. The Captain transmits

a "fire fighter down" message. The crew continues south on Orchard

Lane to a location just short of Highway 78.

The three exit the engine and advise a Hot Shot crew that they have been

burned. The Hot Shot crew provides medical assistance prior to the three

being flown to a hospital burn unit in San Diego for treatment.

INJURIES/DAMAGES

Injuries:

The Fire Fighter had minor inhalation injuries to the respiratory tract

and first degree burns on the face (under the goggles), and small patches

of first-degree burns on the back between the shoulder blades.

Engineer #1 received second-degree burns on the tip of the nose and a

two-inch by three-inch area on the back. First-degree burns were also

sustained on all knuckles of both hands and an additional two-inch by

three-inch area on the back.

The Captain received second-degree burns affecting approximately 28%

of the body including the face, ears, arms, elbows, and legs as well as

sustaining a respiratory inhalation injury.

Engineer #2 died while running for the house and received extensive burns

over most of the body.

Damage:

Plastic lens covers on all four sides of E6162 melted or showed heat

damage. The vinyl hose bed cover for the driver's side pre-connect and

both rear hose bed covers melted. There was no obvious heat damage to

the paint and the engine was driven away from the accident site.

The wood-frame stucco house at 920 Orchard Lane had a rolled paper and

tar roof, and a large wooden deck attached to the north end of the house.

The house burned to the ground after the surviving crew members left the

scene.

SAFETY ISSUES FOR REVIEW

TEN STANDARD FIRE ORDERS APPLICABLE

#1. Keep informed on fire weather conditions and forecasts.

This needs to be an on-going activity based on all available information.

This includes fire weather watches and red flag warnings.

#2. Know what your fire is doing at all times.

This should include the main body of the fire and any fingers and hotspots.

If there is any firing taking place in the area, this fire activity needs

to be monitored also.

#3. Base all actions on current and expected behavior of the

fire.

It is important to consider not only the current and expected behavior,

but consideration should be given to the unexpected or possible worst-case

scenario.

#5. Post lookouts when there is possible danger.

The presence of a posted, dedicated lookout assigned to the division

or area of greatest concern/threat would have allowed for an observation

of the fire in the drainage.

#6. Be alert. Keep calm. Think clearly. Act decisively.

Command presence during times of stress is imperative. The leadership

demonstrated during this event directly saved lives.

#7. Maintain prompt communication with your forces, your supervisor

and adjoining forces.

This needs to be accomplished at all levels within the operation, including

the crew level, strike team / task force level, the division / branch

level and the operational level. If air resources are moved into and out

of an area this needs to be communicated.

#9. Maintain control of your forces at all times.

When positioning, or repositioning resources during a fluid fire environment,

it is critical to ensure that all resources are accounted for, and to

the greatest extent possible, know the location of their adjoining forces

and the tactics being employed.

#10. Fight fire aggressively, having provided for safety first.

Aggressive actions generally place fire fighters in close proximity to

the fire's edge. Safety mitigations must be part of the immediate plan.

In this case safety of the crew was demonstrated by aggressive actions

taken at the structure to create a more favorable position, which included

a safety zone. When reacting to extreme fire behavior accompanied by a

rapidly spreading fire, the safety plan needs to be continually evaluated

and updated. It appears that all of the necessary Personal Protective

Clothing and Equipment was being worn correctly.

18 WATCH OUT SITUATIONS APPLICABLE

#4. You are in an area where you are unfamiliar with local factors

influencing fire behavior.

Out of area / region crews need to be briefed on local conditions and

fire behavior prior to going onto the fireline.

#5. You are uniformed on strategy, tactics and hazards.

All tactics being implemented both within and adjacent to the assigned

division need to be known and communicated to all. This is especially

true of firing operations.

#11. You are in heavy cover with unburned fuel between you and

the fire.

The inability to estimate fire spread in heavy fuels is often cited as

a causal agent in fire line injuries / deaths and is directly related

to Situation #12.

#12. You cannot see main fire and you are not in communication

with anyone who can.

The lack of knowledge about exactly where the leading edge of the fire

is and what it is doing, places those that cannot acquire that information

at considerable risk.

#15. You notice that the wind begins to blow, increase or change

direction.

While often noticed, if not noticed and communicated in time, any required

change in the pre-determined safety plan may not allow for the plan to

be communicated and implemented.

#17. You are away from a burned area where terrain and/or cover

makes travel to safety zones difficult and slow.

The ability to reach a safety zone, as opposed to an area of refuge,

needs to be carefully scrutinized, allowing for a reasonable time frame

under the worst-case situation.

COMMON DENOMINATORS APPLICABLE

When there is an unexpected shift in wind direction or speed.

The unexpected shift in direction and rapid increase in the speed of

the wind were a direct contribution to this accident.

Fires run uphill surprisingly fast in chimneys, gullies, and

on steep slopes.

This fire responded to an upslope / up-canyon influence as it spotted

across the highway and into the upper tributary of a major drainage. The

accident site was located on a high ridge and at the top of a significant

chimney.

L. C. E. S.

Lookouts

Lookouts dedicated to that role need to be identified and have proper

communication ability. The Lookout location, and time they will be in

place, needs to be known by all crews assigned to that division / location.

The use of aerial reconnaissance and aerial lookouts needs to be used

when it is the only viable lookout that can adequately perform the function.

Communications

As prompt radio communication begins to degrade, regardless of the reason,

the propensity to rely on face-to-face communication requires that everyone

realize the increased time it will take to ensure all who need to know

specific information have in fact received it.

Lookouts need to have a clear understanding of desired "trigger

points" and to whom and how they will be communicated.

Although not a common occurrence, on this incident the loss of a repeater

(destroyed by fire) further complicated radio communications.

Command staff must ensure that any and all significant weather information

is broadcast to all levels of the incident organization.

The use of VHF and 800 MHz radio frequencies and the potential for lack

of communication on the incident, specifically at the division level must

be recognized by all personnel. The assignment of multiple tactical frequencies

within a division (air resources, structure group, division tactical channel)

must be known, and/or monitored for critical radio traffic.

Escape Routes

Escape routes that are identified at any given moment, need to be constantly

evaluated and re-evaluated. The utilization of vehicles / structures as

refuge and/or Safety Zones needs to be clearly discussed and assigned

accordingly. Creating additional defensible space around structures must

be included in the re-evaluation of the number, type and location of escape

routes. Escape routes for both vehicular and foot traffic need to remain

viable throughout the operation and during the worst-case scenario.

Safety Zones

Safety zones need to be identified and/or established and communicated

to all who may have to use them. Their size and location needs to be based

on both current and expected fire behavior. While safety zones may be

adequate for what is expected, they need to be applied to the burning

conditions present to ensure they are adequate.

The difference between safety zones and refuge areas needs to be clearly

understood by all who may use them. The pros and cons of each and the

desired sequence of use also need to be communicated.

Safety Zones should allow for the required level of safety from as many

angles as possible.

INCIDENTAL ISSUES FOR REVIEW

1. Emphasize the need to establish a dedicated "Lookout" position

into the ICS organization.

2. Need to review the 10 Standard Orders, 18 Watch Out Situations, and

LCES for specific applicability to wildland/interface operations.

3. Need to address interoperability of communication systems within the

fire service community. Specifically the 800 MHz versus the VHF frequencies.

4. Need to develop systematic process to inform out-of-area/region resources

with local conditions affecting the fire environment.

5. Need to evaluate structure defense philosophies, strategies, and tactics

and incorporate into standardized training, technology and procedures.

6. Approximately 1.5 miles southwest of the entrapment site, 11 fire

fighters were killed in a fire storm on the Inaja Fire. (See Orchard Lane

Vicinity Map) The Inaja Fire started November 25, 1956, under strong Santa

Ana winds, the fatalities occurred when the winds turned to the west.

|