Surviving

Fire Entrapments

Test Results

Also read about engine entrapment incidents:

|

|

Surviving

Fire Entrapments

Comparing Conditions Inside

Vehicles and Fire Shelters |

Montana Burn

The Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation supplied

two engines for the test in southwestern Montana. One was a surplus military

212-ton truck that had been converted to an engine. It was similar to

the engine that was burned over on the Point Fire near Kuna, ID, in 1995,

killing two firefighters inside. The other was a crew carrier pickup that

had been fitted with a slip-on fire tank and pump.

The test burn was conducted in late July in an area of thinned lodgepole

pine slash that had been piled about 5 feet (2 m) high, 8 feet (2 m) wide,

and 200 feet (61 m) long. Air temperatures that day were in the mid-70's

(about 21 °C), with humidities in the low 20's. The engines, fire

shelters, and PPE were laid out beside the edge of the slash piles to

obtain maximum heat load.

An unforecast wind shift just before ignition prevented direct flame

contact on the vehicles and shelters being tested (Figure 22).

Figure 22-Wind prevented

flames from directly contacting vehicles during the test burn near Dillon,

MT.

However, satisfactory results were obtained:

- Maximum air temperature outside the 212-ton engine was 400 °C,

while temperatures inside the cab exceeded 700 °C. The inside of

the engine cab caught fire (Figure 23) and burned, resulting in the

higher temperatures.

Figure 23-Even though flames did not directly contact the 212-ton

truck, its cab caught fire.

- The crew cab truck outside air temperatures were less than 200 °C.

Air temperatures inside the cab exceeded 250 °C because the interior

caught fire.

- Surface temperatures on the fire shelter at the rear of the 212-ton

engine reached 150 °C, although they generally remained in the range

of 100 to 150 °C. Inside surface temperatures remained below 100

°C, except for a momentary spike to 140 °C.

- Air temperatures inside the fire shelter at the rear of the 212-ton

engine were only 40 °C at 1 inch (3 cm) AGL and 75 °C at 12

inches (30 cm) AGL. The shelter had no visible damage.

- The stainless steel prototype shelter in front of the crew cab engine

had outside surface temperatures of 250 °C, and inside surface temperatures

of 220 °C. The free air temperature inside the stainless steel shelter

at 12 inches (30 cm) AGL was 105 °C; the thermocouple at 1 inch

(3 cm) AGL was faulty and did not record.

- The radiometer at the front of the crew cab engine measured a radiant

heat flux of 170 kW/m2, with a prolonged level (longer than 6 minutes)

of 130 kW/m2; the heat flux decreased with the height above the ground.

- The radiometer at the front of the 21/2- ton engine measured a peak

radiant heat flux of 150 kW/m2 at 9 feet (3 m) AGL.

- The cabs of both engines filled with thick smoke. Within a few minutes

after the burn was ignited, the interior of both cabs caught fire from

the radiant heat.

- Protective clothing and equipment was instrumented with thermocouples

and laid between the fire shelters and the engines. The items selected

(trousers, shirts, flight suits, and coveralls) were placed over a 5-gallon

water bag that had been covered with a 100% cotton T-shirt (see Test

Procedures and Methods).

- Nomex trousers recorded an outside surface temperature of 160

°C and an inside temperature of 20 °C, with no visible damage

to the trousers.

- A Nomex fire shirt recorded an outside temperature of 100 °C,

and an inside temperature of 70 °C, with no visible damage.

- Although the Nomex had some heat discoloration, it retained its

structure and did not break apart or catch fire.

- FR cotton coveralls from the Northwest Territories were not instrumented,

but they were laid out immediately adjacent to the Nomex shirt.

They were partially consumed by fire ignited by radiant heat.

- A GSA firefighter's hardhat (Model 5100-P) was placed on the ground

beside the fire shelter in front of the crew cab engine. It showed

significant melting for about 5 inches (13 cm) from its edge, but

the rest of the helmet showed no melting or damage (Figure 24).

Figure 24-This hardhat shows the difference a few inches can make

at ground level. The hardhat melted where it was closest to the fire,

but wasn't damaged just a few inches away from the heat.

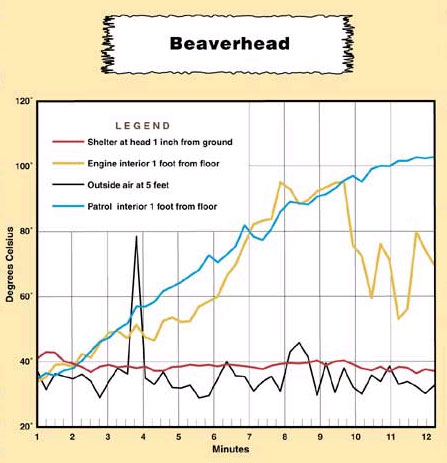

BEAVERHEAD

<<< continue

reading—Surviving Fire Entrapments, Discussion >>>

|