1967 Task Force Report

2005 Fire Prevention and Safety grant application

|

| The following “short feature”

appeared in Volume

52, Number 4, 1991 (.pdf file, 2.5 mb) of Fire

Management Notes.

At the time, Paul Gleason was the North Roosevelt fire management

officer, USDA Forest Service, Arapaho and Roosevelt National Forests,

Redfeather Ranger District, Fort Collins, CO. |

LCES—a Key to Safety in the Wildland Fire Environment

by Paul Gleason

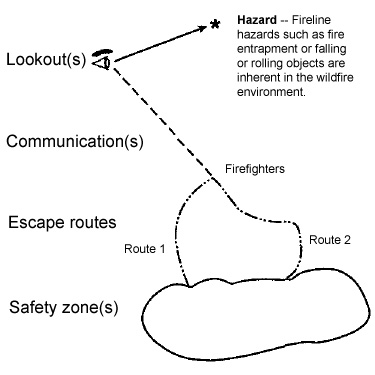

L—Lookout(s)

C—Communication(s)

E—Escape routes

S—Safety zone(s)

LCES—a System for Operational Safety.

In the wildland fire environment, where four basic safety hazards confront

the firefighter—lightning, fire-weakened timber, rolling rocks,

and entrapment by running fires—LCES is key to safe procedure for

firefighters. LCES stands for “lookout(s),” “communication(s),”

“escape routes,” and “safety zone(s)” —

an interconnection each firefighter must know. Together the elements of

LCES form a safety system used by firefighters to protect themselves.

This safety procedure is put in place before fighting the fire: Select

a lookout or lookouts, set up a communication system, choose escape routes,

and select safety zone or zones. (See diagram.)

In operation, LCES functions sequentially—it's a self-triggering

mechanism: Lookouts assess—and reassess—the fire environment

and communicate to each firefighter threats to safety; firefighters use

escape routes and move to safety zones. Actually, all firefighters should

be alert to changes in the fire environment and have the authority to

initiate communication.

Key Guidelines.

LCES is built on two basic guidelines:

-

Before safety is threatened, each firefighter must be informed how

the LCES system will be used.

-

The LCES system must be continuously reevaluated as fire conditions

change.

How To Make LCES Work.

Train lookouts to observe the wildland fire environment and to recognize

and anticipate fire behavior changes. Position lookout or lookouts where both the hazard and the firefighters

can be seen. (Each situation—the terrain, cover, and fire size—determines

the number of lookouts that are needed. As stated before, every firefighter

has both the authority and responsibility to warn others of threats

to safety.) Set up communications system—radio, voice, or both—by

which the lookout or lookouts warn firefighters promptly and clearly

of approaching threat. (Most often the lookout initiates a warning that

is subsequently passed down to each firefighter by “word-of-mouth.”

It is paramount that every firefighter receive the correct message in

a timely manner.) Establish the escape routes (at least two)—the paths the firefighters

take from threatened position to area free from danger—and make

them known. (In the Battlement Creek 1976 fire, three firefighters lost

their lives after retreat along their only escape route was cut off

by the advancing fire.) Reestablish escape routes as their effectiveness decreases. (As a

firefighter works along the fire perimeter, fatigue and distance increases

the time required to reach a safety zone.) Establish safety zones—locations where the threatened firefighter

may find adequate refuge from the danger. (Fireline intensity, air flow,

and topographic location determine a safety zone’s effectiveness.

Shelter deployment sites have sometimes been termed, improperly and

unfortunately, “safety zones.” Safety zones should be conceptualized

and planned as a location where no shelter will be needed. This does

not imply that a shelter should not be deployed if needed, only that

if there is a deployment, the safety zone location was not truly a safety

zone.)

A Final Word.

The LCES system approach to fireline safety is an outgrowth of my analysis

of fatalities and near-misses for over 20 years of active fireline suppression

duties. LCES simply refocuses on the essential elements of the standard

FIRE ORDERS. Its use should be automatic in fireline operations. All firefighters

should know LCES, the Lookout-Communication-Escape routes-Safety zone

interconnection.

|