The Human Factors Analysis and Classification System—HFACS Cover

and Documentation

Introduction

1. Unsafe Acts

2. Preconditions

for Unsafe Acts

3. Unsafe Supervision

4. Organizational

Influences

Conclusion

References

HFACS and Wildland Fatality Investigations

Hugh Carson wrote this

article a few days after the Cramer Fire

Bill Gabbert wrote this article following the release of the Yarnell Hill Fire ADOSH report

A Roadmap to a Just Culture:

Enhancing the Safety Environment

Cover

and Contents

Forward by James Reason

Executive Summary

1. Introduction

2. Definitions and Principles of a Just Culture

3. Creating a Just Culture

4. Case Studies

5. References

Appendix A. Reporting Systems

Appendix B. Constraints to a Just Reporting Culture

Appendix C. Different Perspectives

Appendix D. Glossary of Acronyms

Appendix E. Report Feedback Form

Rainbow Springs Fire, 1984 — Incident Commander Narration

Introduction

Years Prior

April 25th

Fire Narrative

Lessons Learned

Conclusion

Tools to Identify Lessons Learned

An FAA website presents 3

tools to identify lessons learned from accidents. The site also

includes an animated

illustration of a slightly different 'Swiss-cheese' model called "defenses-in-depth."

|

A Roadmap to a Just Culture:

Enhancing the Safety Environment

Prepared by: GAIN Working Group E,

Flight Ops/ATC Ops Safety Information Sharing

First Edition • September 2004

2. Definitions and Principles of a Just Culture

2.1 Definition of Just Culture

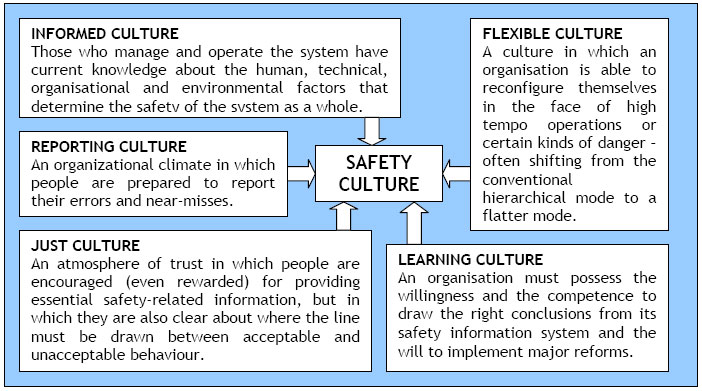

According to Reason (1997), the components of a safety culture include:

just, reporting, learning, informed and flexible cultures. Reason describes

a Just

Culture as an atmosphere of trust in which people are encouraged (even

rewarded) for providing essential safety-related information, but in

which they are

also clear about where the line must be drawn between acceptable and

unacceptable behavior (See Figure 1).

A “Just Culture” refers to a way of safety thinking that promotes

a questioning attitude, is resistant to complacency, is committed to excellence,

and fosters both personal accountability and corporate self-regulation in

safety matters.

A “Just” safety culture, then, is both attitudinal as well as

structural, relating to both individuals and organizations. Personal attitudes

and corporate style can enable or facilitate the unsafe acts and conditions

that are the precursors to accidents and incidents. It requires not only actively

identifying safety issues, but responding with appropriate action.

Figure 1. Based on Reason (1997) The Components of Safety Culture: Definitions

of Informed, Reporting, Just, Flexible and Learning Cultures

2.2 Principles of a Just Culture

This section discusses some of the main

issues surrounding Just Culture, including the benefits of having a learning

culture versus a blaming culture; learning from unsafe acts; where the

border between “acceptable” and “unacceptable” behavior should

be; and ways to decide on culpability.

Evaluating the benefits of punishment versus learning

A question that organizations should ask themselves is whether or not the

current disciplinary policy is supportive to their system safety efforts.

- Is it more worthwhile to reduce accidents by learning from incidents

(from incidents being reported openly and communicated back to the

staff) or by punishing people for making mistakes to stop them from making

mistakes

in the future?

- Does the threat of discipline increase a person’s

awareness of risks or at least increase one’s interest in assessing

the risks? Does this heightened awareness outweigh the learning through punishment?

- By

providing safety information and knowledge, are people more interested

in assessing the risks? Does this heightened awareness outweigh the learning

through punishment?

- How does your system treat human error? Does

your system make an employee aware of their mistake? Can an employee

safely come

forward if they make a mistake, so that your organization can learn

from the event?

Positions for and against punishment as a means of learning are illustrated

below:

In favor of punishment of the negligent actor: “when people have

knowledge that conviction and sentence (and punishment) may follow conduct

that inadvertently creates improper risk, they are supplied with an additional

motive to take care before acting, to use their facilities and draw on their

experience in gauging the potentialities of contemplated conduct. To some

extent, at least, this motive may promote awareness and thus be effective

as a measure of control.” (American Law Institute Model Penal Code,

Article 2. General Principles of Liability, Explanatory Note 2.02, 1962).

Against punishment of the negligent actor: “a person acts “recklessly” with

respect to a result if s/he consciously disregards a substantial risk and

acts only “negligently” if s/he is unaware of a substantial risk

s/he should have perceived. The narrow distinction lies in the actor’s

awareness of risk. The person acting negligently is unaware of harmful consequences

and therefore is arguably neither blameworthy nor deterrable” (Robinson & Grall

(1983) Element Analysis in Defining Criminal Liability: The Model Penal Code

and Beyond. 35 Stan. L. Rev. 681, pp 695-96).

Learning from unsafe acts

A Just Culture supports learning from unsafe acts. The first goal of any

manager is to improve safety and production. Any event related to safety,

especially human or organizational errors, must be first considered as a valuable

opportunity to improve operations through experience feedback and lessons

learnt (IAEAa).

Failures and ‘incidents’ are considered by organizations with

good safety cultures as lessons which can be used to avoid more serious events.

There is thus a strong drive to ensure that all events which have the potential

to be instructive are reported and investigated to discover the root causes,

and that timely feedback is given on the findings and remedial actions, both

to the work groups involved and to others in the organization or industry

who might experience the same problem. This ‘horizontal’ communication

is particularly important (IAEAb).

Organizations need to understand and acknowledge that people at the sharp

end are not usually the instigators of accidents and incidents and that they

are more likely to inherit bad situations that have been developing over a

long period (Reason, 1997). In order that organizations learn from incidents,

it is necessary to recognize that human error will never be eliminated; only

moderated. In order to combat human errors we need to change the conditions

under which humans work. The effectiveness of countermeasures depends on the

willingness of individuals to report their errors, which requires an atmosphere

of trust in which people are encouraged for providing essential safety-related

information (Reason, 1997).

2.3 Four types of unsafe behaviors

Marx (2001) has identified four types

of behavior that might result in unsafe acts. The issue that has been

raised by Marx (2001) and others is that not all of these behaviors necessarily

warrant

disciplinary sanction.

- Human error – is when there is general agreement that the individual

should have done other than what they did. In the course of that conduct where

they inadvertently caused (or could have caused) an undesirable outcome, the

individual is labeled as having committed an error.

- Negligent conduct – Negligence

is conduct that falls below the standard required as normal in the community.

Negligence, in its legal sense, arises both in the civil and criminal liability

contexts. It applies to a person who fails to use the reasonable level of

skill expected of a person engaged in that particular activity, whether by

omitting to do something that a prudent and reasonable person would do in

the circumstances or by doing something that no prudent or reasonable person

would have done in the circumstances. To raise a question of negligence, there

needs to be a duty of care on the person, and harm must be caused by the negligent

action. In other words, where there is a duty to exercise care, reasonable

care must be taken to avoid acts or omissions which can reasonably be foreseen

to be likely to cause harm to persons or property. If, as a result of a failure

to act in this reasonably skillful way, harm/injury/damage is caused to a

person or property, the person whose action caused the harm is liable to pay

damages to the person who is, or whose property is, harmed.

- Reckless conduct – (gross

negligence) is more culpable than negligence. The definition of reckless conduct

varies between countries, however the underlying message is that to be reckless,

the risk has to be one that would have been obvious to a reasonable person.

In both civil and criminal liability contexts it involves a person taking

a conscious unjustified risk, knowing that there is a risk that harm would

probably result from the conduct, and foreseeing the harm, he or she nevertheless

took the risk. It differs from negligence (where negligence is the failure

to recognize a risk that should have been recognized), while recklessness

is a conscious disregard of an obvious risk.

- Intentional “willful” violations – when

a person knew or foresaw the result of the action, but went ahead and did

it anyway.

2.4 Defining the border of “unacceptable behavior”

The

difficult task is to discriminate between the truly ‘bad behaviors’ and

the vast majority of unsafe acts to which discipline is neither appropriate

nor useful. It is necessary to agree on a set of principles for drawing

this line:

Definition of Negligence: involved a harmful consequence that a ‘reasonable’ and ‘prudent’ person

would have foreseen.

Definition of Recklessness: one who takes a deliberate and unjustifiable

risk.

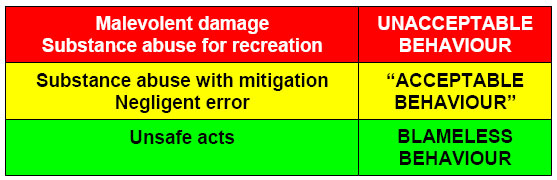

Reason (1997) believes that the line between “culpable” (or “unacceptable”)

and “acceptable” behavior should be drawn after ‘substance

abuse for recreational purposes’ and ‘malevolent damage.’

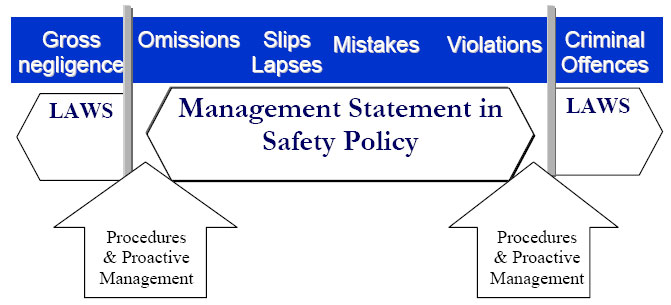

The following figure (Figure 2) illustrates the borders between “acceptable” and “bad” behaviors,

where statements in the safety policy can deal with human error (such as omission,

slips etc), and where laws come into play when criminal offenses and gross

negligence are concerned. Procedures and proactive management can support

those situations that are less clear, at the borders.

Figure 2. Defining the borders

of “bad behaviors” (From

P. Stastny Sixth GAIN World Conference, Rome, 18-19 June, 2002)

2.5 Determining ‘culpability’ on an individual case basis

In

order to decide whether a particular behavior is culpable enough to require

disciplinary action, a policy is required to decide fairly on a case-by-case

basis. Three types of disciplinary policy are described below (Marx,

2001). The third policy provides the basis for a Just Culture. Reason’s Culpability

Decision-Tree follows, presenting a structured approach for determining culpability.

This is followed by Hudson’s (2004) expanded Just Culture diagram, which

integrates types of violations and their causes, and accountabilities at all

levels of the organization.

- Outcome-based Disciplinary Decision Making – focuses

on the outcome (severity) of the event: the more severe the outcome, the

more blameworthy the

actor is perceived. This system is based on the notion that we can totally

control

the outcomes from our behavior. However, we can only control our intended

behaviors to reduce our likelihood of making a mistake, but we cannot

truly control when and where a human error will occur. Discipline may

not deter

those who did not intend to make a mistake (Marx, 2001).

- Rule-based Disciplinary Decision Making – Most high-risk industries have

outcome-based rules (e.g. separation minima) and behavior-based rules

(e.g. work hour limitation). If either of these rules is violated, punishment

does

not necessarily follow, as for example, in circumstance where a large

number of the rules do not fit the particular circumstances. Violations

provide critical

learning opportunities for improving safety – why, for example,

certain violations become the norm.

- Risk-based Disciplinary Decision Making – This method considers

the intent of an employee with regard to an undesirable outcome. People

who act

recklessly, are thought to demonstrate greater intent (because they

intend to take a significant and unjustifiable risk) than those who demonstrate

negligent

conduct. Therefore, when an employee should have known, but was unaware,

of the risk s/he was taking, s/he was negligent but not culpably so, and

is therefore

would not be punished in a Just Culture environment.

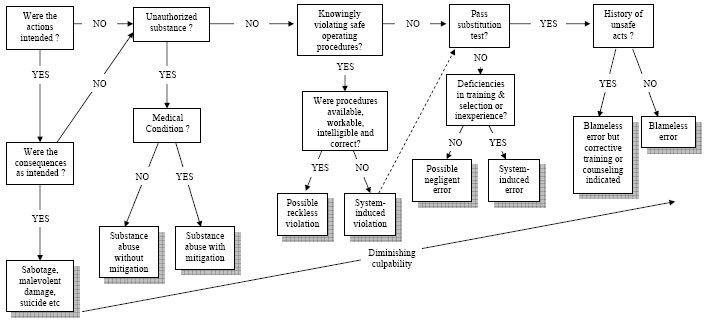

Reason’s Culpability Decision-Tree – Figure 3 displays a decision tree

for helping to decide on the culpability of an unsafe act. The assumption

is that the actions under scrutiny have contributed to an accident or to

a serious incident. There are likely to be a number of different unsafe acts

that contributed to the accident or incident, and Reason (1997) believes

that

the decision tree should be applied separately to each of them. The concern

is with individual unsafe acts committed by either a single person or by

different people at various points of the event sequence. The five stages

include:

-

Intended act: The first question in the decision-tree relates to intention,

and if both actions and consequences were intended, then it is possibly

criminal behavior which is likely to be dealt with outside of the company

(such as

sabotage or malevolent damage).

-

Under the influence of alcohol or drugs known to impair

performance at the time that the error was committed. A distinction is

made between substance abuse with and without ‘reasonable

purpose (or mitigation), which although is still reprehensible, is

not as blameworthy

as taking drugs for recreational purposes.

-

Deliberate violation of the rules and did the system

promote the violation or discourage the violation; had the behavior become

automatic or part

of the ‘local working practices.’

-

Substitution test: could a different

person (well motivated, equally competent, and comparably qualified)

have made the same error under similar circumstances (determined by

their peers).

If “yes” the person who made the error is probably blameless,

if “no”, were there system-induced reasons (such as insufficient

training, selection, experience)? If not, then negligent behavior

should be considered.

-

Repetitive errors: The final question asks whether the

person

has committed unsafe acts in the past. This does not necessarily

presume culpability, but it may imply that additional training or counseling

is

required.

Reason’s

Foresight test: provides a prior test to the substitution test described above,

in which culpability is thought to be dependent upon the kind of behavior

the person was engaged in at the time (Reason and Hobbs, 2001).

The type of question that is asked in this test is:

— Did the individual knowingly engage in behavior that an average

operator would recognize as being likely to increase the probability

of making

a safety-critical error?

If the answer is ‘yes’ to this question in any of the following

situations, the person may be culpable. However, in any of these situations,

there may be other reasons for the behavior, and thus it would be necessary

to apply the substitution test.

- Performing the job under the influence of a drug or substance known

to impair performance.

- Clowning around whilst on the job.

- Becoming

excessively fatigued as a consequence of working a double shift.

- Using

equipment known to be sub-standard or inappropriate.

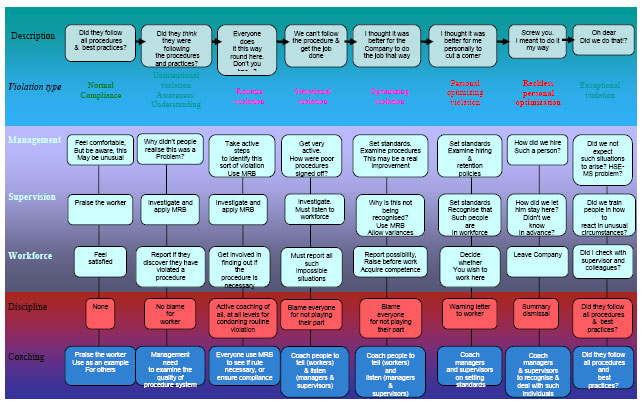

Hudson’s

Version of the Just Culture Diagram (Figure 4)

Hudson (2004) expands Reason’s Culpability Decision tree, using a more

complex picture that integrates different types of violation and their causes.

This model starts from the positive, indicating that the focus of priority.

It defines accountabilities at all levels and provides explicit coaching definitions

for failures to manage violations. This approach (called “Hearts and

Minds”) includes the following four types of information to guide those

involved in deciding accountability:

- Violation type - normal compliance to exceptional violation

- Roles of

those involved - managers to workers

- Individuals -the reasons for

non-compliance

- Solutions - from praise to punishment

Figure 3. From

Reason (1997) A decision tree for determining the culpability of unsafe

acts. p209 (click for larger image)

Figure 4. Hudson’s

refined Just Culture Model (From the Shell “Hearts

and Minds ” Project, 2004) (click for larger image)

Determining Negligence: an example (SRU, 2003)

- Was the employee aware of what he or she has done? NO

- Should

he have been aware? YES

- Applying the “Substitution Test”:

Substitute the individual concerned with the incident with someone else

coming from the same area of work and having comparable experience and

qualifications. Ask the “substituted” individual: “In

the light of how events unfolded and were perceived by those involved

in real time, would you have behaved any differently?” If the

answer is “probably not”, then apportioning blame has no

material role to play.

- Given the circumstances that prevailed at the

time, could you be sure that you would not have committed the

same or similar type of unsafe act? If the answer again is “probably not”,

the blame is inappropriate.

|

Dealing with repetitive errors

Can organizations afford someone who makes repeated errors while

on the job? The answer to this question is difficult as the causes

of repeat errors have two different sources:

1) An individual may be performing a specific task that is very prone

to error. Just as we can design systems to minimize human error through

human factors, we can design systems that directly result in a pronounced

rate of error. Therefore it is critical for the designers to be aware

of the rate of error.

2) A source of repeated error may be with the individual. Recent traumatic

events in one’s life or a significant distraction in life can

cause some individuals to lose focus on the details of their work, possibly

leading to an increased rate of error. In such cases, it may be an appropriate

remedy to remove the individual from his current task or to supplement

the task to aid in controlling the abnormal rate of error. |

What to do with lack of qualification?

An unqualified employee can cross the threshold of recklessness if

he does not recognize himself as unqualified or as taking a substantial

risk in continuing his current work. Lack of qualification may only

reveal that an individual was not fully trained and qualified in the

job and therefore show that it is a system failure not to have ensured

that the appropriate qualifications were obtained. |

<<< continue

reading—A Roadmap to a Just Culture, Creating a Just Culture >>>

Reprinted by permission

from the Global Aviation Information Network.

|